Publications

Publications

Ouvrages

Ouvrages

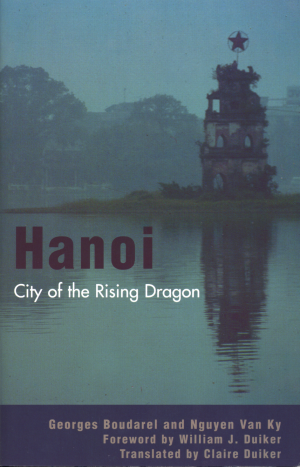

Hanoi. City of the Rising Dragon.

Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.,

2002, 187 p.

with G. Boudarel (1926-2003), foreword by William J. Duiker,

translated by Claire Duiker

Hanoi. City of the Rising Dragon.

Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.,

2002, 187 p.

with G. Boudarel (1926-2003), foreword by William J. Duiker,

translated by Claire Duiker

§ A City which Remembers

The city under the Waters

The city of today was built, literally and figuratively, along the bends

of the Song Hong, or Red River, which cuts across Hanoi from the

northwest to the southeast. A high iron content gives the river its

brick-red color and its name. It has its source in the mountains of

southwest China and is joined by several tributaries around Mount Ba

Vi, one of which is the Black River (Song Da).

The

region around Hanoi was originally swampy and riddled with lakes,

which remained as vestiges of the river’s previous paths. The

current configuration of the city was carved out in part by the sea

and the powerful Red River—whose floods sometimes altered the

shape of the city overnight—and in part by the lush vegetation,

whose traces can still be found in certain place names, like Gia Lam

(forest of banyans) and Mai Lam (forest of plum trees). As a result,

the inhabitants of this flood plain area have always maintained a

high concern for the construction and integrity of the dykes that

protect them. Even today, the city lies below the water level in

times of flooding.

In centuries past, Hanoi was in a sense the Venice of the Far East, as

people traveled from place to place by boat along a complex network

of lakes, streams, and canals. The presence of water shaped both the

material and cultural life of the city, carrying with it both life

and death, to the point where the word “country” in

popular language is

dat nuoc (earth-water). The Vietnamese

people have always lived this duality. Since they could not

definitively master the water, they learned to make it their ally and

an integral part of their nation. Once again, language provides a key

for understanding the importance of water to the people of Hanoi: the

term for “our country” (

nuoc nha) literally means

“water-home,” and “the state” (

nha nuoc)

means “home-water.”

From

its founding in 1010 until the 18

th century, Hanoi was

composed of two distinct parts. The Imperial City was in the center,

ringed by the fortified walls of the citadel, and including the

Forbidden City. Surrounding this was a group of neighborhoods which

housed merchants, artisans, and the imperial servants. Writings such

as Nguyen Trai’s

Dia du chi [Treatise on Geography]

describe the scope of the city in the 15

th century. The

Imperial City underwent many changes throughout history, as best

illustrated by the successive constructions of its citadel: the old

fortress of Dai La [Great Citadel], built in the 9

th

century, was replaced by the citadel of Thang Long in the 11

th

century; this, in turn, was then enlarged by Olivier du Puymanel in

1805 under the Nguyen dynasty to emulate the French style of Vauban

As the seat of power, the Imperial City was laid out in the form of a

square, a reference to Confucian cosmology which holds that the

square symbolized the earth while the sky was represented by a

circle. It was delimited in the north by West Lake, in the south by

what is now the Street of the Bridge of Paper, in the east by what is

now called Ba Dinh Square, and in the west by the To Lich River.

Outside of this square lay old Hanoi, with its thirty-six commercial

neighborhoods. The capital was thus protected by natural defenses: on

the north and northeast by the Red River, separated from West Lake by

a dyke, and on the west by the To Lich River. Moreover, the fertility

of the alluvial soil was undoubtedly one of the reasons that

successive Vietnamese dynasties remained in Hanoi until the 19

th

century, taking advantage of the richness of the soil to develop and

prosper.

A city of Legend

One

of Hanoi’s most famous legends is that of Returned Sword Lake.

It is said that a mythical tortoise gave its sacred sword to king Le

Loi (reigned 1428 – 1433 ),

allowing him to expel the occupying forces of the Chinese Ming

Dynasty in the 15

th century after ten years of resistance.

The people from Hanoi also love to tell stories about the

etymological origins of Thang Long, the city’s first name. When

the boats of Ly Cong Uan, the founder of the 11

th century

Ly dynasty, arrived on the site from Hoa Lu, a golden dragon appeared

to welcome them and then flew off into the sky. This good omen

convinced the king to build the capital there, calling it Thang Long,

which means “the ascending dragon.”

The

dragon is an important symbol for the Vietnamese. One of their

national legends tells of the city’s ancestors, the mythical

couple Lac Long Quan and Au Co, the former a descendent of dragons

and the latter of fairies. Popular belief also contends that dragons

can cause rain, which is indispensable for growing rice. Lastly, the

dragon is a symbol of imperial power in Chinese ideography, a writing

system adopted by the Vietnamese court. The name Thang Long thus

brought together the monarchy and the common people, a meaning which

was ruptured in the 19

th century by the transfer of the

capital to Hue. The Nguyen dynasty then emptied the city of its

symbolic role by renaming it Ha Noi (the city in the water).

The

origin of West Lake can claim two legends. One goes back to the

founding of the country, and tells of how the region of Hanoi was

terrorized by a fox with nine tails. Lac Long Quan, the dragon god,

entered into battle with the fox to drive it from the area. The fox

fled and left behind him the tracks of his many tails, which then

collapsed and gave birth to West Lake. Some older story-tellers offer

another version: there once was a giant named Khong Minh Khong who

went to China to find a cure for a princess who had fallen ill. Out

of gratitude, the king offered him a piece of black bronze from the

royal coffers. Khong Minh Khong transformed the bronze into a bell,

whose peals could be heard all the way to China. A golden buffalo

heard the bell and thought he recognized the lowing of his mother, so

traveled from China to Vietnam, following the sounds of the bell. His

tracks became the river Kim Nguu (golden buffalo), a former arm of

the river To Lich; and the forest of

lim,

which was now trampled and flattened, became West Lake.

The

city of today was built, literally and figuratively, along the bends

of the Song Hong, or Red River, which cuts across Hanoi from the

northwest to the southeast. A high iron content gives the river its

brick-red color and its name. It has its source in the mountains of

southwest China and is joined by several tributaries around Mount Ba

Vi, one of which is the Black River (Song Da).

Temples: The Guardians of History

Hanoi

has more than a thousand historical buildings, with some 579 communal

houses ,

676 pagodas, and 261 temples spread out across the city. Since 1954,

more than two hundred have been classified as historical sites.

During the Ly dynasty, a number of Buddhist religious structures were

built. One of the most famous, the One Pillar Pagoda, was built in

1049 in the shape of a lotus, a symbol of Buddha’s

enlightenment. The pagoda was built in the middle of a pond on the

east side of the Imperial City and has been destroyed and rebuilt

many times. It was completely demolished by the French army during

the Franco-Vietminh War and was entirely rebuilt. Then in the 1970s,

a senior government official suggested that it be torn down because

it didn’t conform with the new mausoleum being built to house

the remains of Ho Chi Minh. The outspoken historian Tran Quoc Vuong

dared to protest against the proposal and was reprimanded by ignorant

opportunists hoping to impress key leaders. Fortunately, however,

other protests followed and the idea was finally abandoned.

A

short distance away to the south stands the Temple of Literature (Van

Mieu), built in 1076 in homage to Confucius and his disciples. The

site also served as an academy where court-appointed scholars could

meet to discuss classical literature. Shortly afterwards, the

Imperial Academy (Quoc Tu Giam) was built. Considered to be the

country’s first university, it attracted hundreds of students

who moved into the surrounding areas in order to profit from its

prestige. In 1442, graduates of the mandarinal competitions were

celebrated in inscriptions on stone tablets which were erected upon

the back of a sculpted tortoise, the symbol of longevity. The first

tablets were erected in 1484 under the reign of Le Thanh Tong (1460 –

1497), a ruler known for his humanism and erudition.

On

the shores of West Lake in the extreme northeast of the city, at the

beginning of what is now Thanh Nien Street (the Avenue of the Grand

Buddha in colonial times), is the temple of Quan Thanh. This Taoist

structure was built under the Ly in the 11

th century and

was originally dedicated to an ancient protector-spirit. It also

served as one of the sixteen gateways to the city. In 1677 a bronze

statue of the spirit, four meters (13 feet) high, was erected inside.

On the shores of Bay Mau Lake (Lake of Seven Mau ),

another temple was built in the 12

th century, dedicated to

the two Trung sisters. These two heroines tried in vain to evict

Chinese occupying forces in the 1

st century. They

committed suicide by plunging into a river in order to escape

humiliation.

To

the west of the Imperial City are two other historical monuments

dating from the 12

th century: the Temple of the Reclining

Elephants, now located in a zoological park, and the Lang Pagoda,

situated a bit farther south. The former was erected to protect the

western side of the capital, while the latter is known for its

picturesque location and ancient statuary, some of which date back to

the 17

th century. It is still in use today, and is the

site of one of Hanoi’s most popular annual festivals.

We

can now see that the Hanoi of today was shaped by the dynasty that

founded it. The dynasties that followed did little but preserve it,

renovate it, and construct palaces for various dignitaries. None of

these other buildings, however, could withstand the violence of

history. In 1216, the struggle between rival factions of the

declining Ly dynasty provoked a fire and the destruction of the

Imperial City, which later had to be rebuilt by the Tran dynasty

(1225 – 1400). From the 16

th – 18

th

century, royal palaces were built outside of the old Imperial City

because of the fighting between the reigning dynasty of the Le,

reduced to a nominal function, and the Trinh lords (an aristocratic

clan which had seized power at court) who held real power. This

infighting between the ruling classes led to chaos and political

instability, including the assassinations of several Le kings by the

Trinh lords. In 1623, one of the latter burned down the Imperial

City. In 1787, the last reigning Le ruler called for assistance from

the Qing Dynasty in Beijing, but the Tay Son brothers, leaders of a

rebel faction which had taken control in the South, took advantage of

the instability to intervene and liberate the capital from its

Chinese occupiers. In 1789, the battle of Dong Da (named for a hill

situated several kilometers to the south of Hanoi) put an end to the

Chinese intervention .

Notes

|

Sommaire de la rubrique

|

Haut de page

|

Suite

|