Publications

Publications

Ouvrages

Ouvrages

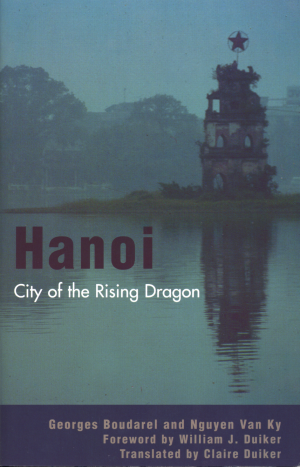

Hanoi. City of the Rising Dragon.

Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.,

2002, 187 p.

with G. Boudarel (1926-2003), foreword by William J. Duiker,

translated by Claire Duiker

Hanoi. City of the Rising Dragon.

Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.,

2002, 187 p.

with G. Boudarel (1926-2003), foreword by William J. Duiker,

translated by Claire Duiker

§ A City which Remembers

Rural City or Urban Village

The

thousand-year-old city was also shaped by its people, who gave it a

soul and a cultural richness that softened the more austere

contributions of the scholarly community. Western travelers in the

17

th century estimated the number of homes in the city at

20,000, which corresponds to a population of around 100,000

inhabitants. By the 19

th century, though, there were no

more than 60,000 people living in Hanoi. This is undoubtedly due to

the transfer of the capital to Hue, which emptied the city of a

substantial part of its population.

The

French loved to repeat that “Hanoi was a big village,” a

remark which actually has some truth to it. There has always been a

constant influx of people from rural areas into the city, the numbers

varying over the centuries according to political, economic, and

social conditions. This steady migration, however, never became an

exodus, since the countryside remained a place of security and refuge

in case of war or social strife. But the city always exercised a

powerful pull on surrounding villages because of its reputation as an

active place of commerce. During the colonial era, the influx of

destitute villagers was so great that the municipality of Hanoi had

to pick them up every month by the hundreds and place them in a

shelter for the homeless at Bach Mai, on the outskirts of town. This

trend continues today as poor peasants arrive daily from the Delta,

exacerbating an already heavy population density. On the outskirts of

the city one still finds many beggars from Thai Binh, a Delta

province that has been overpopulated for centuries.

The

rural population that moved into the city did not, however, abandon

their customs, traditions, or way of life. They brought with them a

whole host of social and spiritual practices from their native

regions which helped them to preserve the past while confronting the

future. Many came to the city accompanied by their families,

sometimes even their whole clan, and sought employment as artisans or

merchants, without ever abandoning their habits of daily village

life. Many have retained the physical mannerisms of their region,

revealing an entire state of mind in a simple gesture. The way some

recent arrivals squat, for example, with their feet planted on low

stools or on a chair at a theater, reveals a certain nonchalance and

carefree attitude towards the future which is characteristic of their

region.

Street Life in Hanoi: the phuong

If the village is the heart of rural life, its urban counterpart is the

phuong—a

word which is usually translated by

“neighborhood” and whose origin dates to the 13

th

century. The

phuong was much more than an administrative zone,

however, as each one included one or more trade associations which

usually came from the same village. They were a kind of

multidimensional space which, like the village, had their own

customs, festivals, cults, spirits, and territory. These

phuong

sprang up and flourished outside of the imperial walls. One of the

more classic examples is old Hanoi itself, bordered to the east by

the Red River, to the south by the southern border of Returned Sword

Lake—the old Petit Lac (small lake) of colonial times, which

used to be much larger than it is now—and to the west by the

fortifications of the Imperial City.

The

growth and development of these working-class neighborhoods in Hanoi

were based mainly on two factors: family ties and professional

skills. Hang Dao Street, for example, known since colonial times as

the Street of Silk, is occupied by silk merchants who sell

merchandise bought in neighboring areas specialized in the making of

silk.

It is the same for many other streets in Hanoi..

The

origin of the

phuong also had a social dimension. In order to

combat isolation and marginalization, immigrants from the countryside

worked together in an effort to constitute an economic and social

force. Without ever severing ties with their native regions, these

neighborhoods served as a kind of relay point between the two worlds.

In this way, immigrants lived a sort of double life: their social

life revolved around the city while their hearts remained in the

countryside. The countryside served as a meeting place for families,

where life was organized according to the rhythm of the major

holidays like Tet (the lunar new year) or the anniversary of an

ancestor’s death. It was also used as a kind of haven, whereby

the scholar who found himself in disagreement with those in power

could always return to his native village in order to avoid

confrontation.

These

city streets are much more than addresses for the people of Hanoi,

they also carry with them traces of the city’s history: like 10

Pho Hang Dao, for example. In 1907 it housed the seat of the

Dong

Kinh Nghia Thuc movement (Tonkin Free School), run by Luong Van

Can and other scholars who were at odds with traditional teaching

methods. Using

quoc ngu

as a new vehicle of instruction, they offered free courses, day and

night, to anyone who wanted to learn about the modern spirit. This

school also served as a cover for anti-French political activities,

and was forced to close its doors by the local authorities after

several months of operation. Like Pho Hang Dao, just about every

street in Hanoi bears witness to elements of the city’s

history.

The Spirit of the Streets

The

names of streets tell us a lot about the past, especially about the

importance of water to the city. Thus we find Hang Be Street (Street

of Rafts), which was situated on a pier, and Hang Buom Street (Street

of Sails), which was devoted to the business of boating sails. Until

the 13

th century there were canoe races on the lakes and

rivers of the city, the likes of which one can still see in Laos,

Cambodia, and Thailand. These boats probably navigated heavy river

traffic up the Red River to old Thang Long, which even then was an

important crossroads for trade and commerce.

From

the 19

th century until the Sino-Vietnamese conflict in

1979, the Street of Sails was especially known for its Chinese

restaurants which had set up there in the 17

th century.

Chinese residents were also grouped in the old Phuc Kien Street,

named for their home province of Fujian. It is now called Lan Ong

Street, after an 18

th century pharmacist who specialized

in traditional medicine, and shares with nearby Thuoc Bac Street

(Street of Chinese Medicine) the specialty of traditional medicines.

With the outbreak of hostilities at the Vietnamese border, the

Chinese community of Hanoi was taken hostage and its people were

forced to pack their bags and move out.

The

Street of Sails is famous for an edifice that is older than the city

itself, Bach Ma Temple (Temple of the White Horse), which dates back

to the 9

th century. According to legend, when Ly Cong Uan,

founder of the Ly dynasty, transferred the capital from Hoa Lu to

Thang Long, he decided to build a fortress for their protection; but

the fortress periodically collapsed. The young monarch called for a

solemn ceremony to invoke protector-spirits who could help him in his

enterprise. A white horse then emerged from the temple, made one

circle around the fortress, and returned inside. The emperor

understood the message and ordered the fortifications to be erected

along the tracks left by the spirit-animal, and the temple thereupon

remained standing. To show his thanks, he elevated the horse to the

rank of protector-spirit of the capital.

The

Temple of the White Horse also had a second function, serving as the

eastern gate of the city. Abandoned and left in ruins for decades as

part of the fight against superstition, the temple has recently been

renovated and given back to the people of the neighborhood who are

once again bringing it back to life.

Hang

Trong Street (Street of Drums, renamed Avenue Jules Ferry by the

colonists) presents a different case, where the shopkeeper was also

the artisan. The street was once inhabited by three guilds: the drum

makers from Hai Hung province fifty kilometers [31 miles] to the east

of Hanoi; the parasol makers from the village of Dao Xa, in Ha Tay

province, some thirty kilometers [19 miles] to the south of the

capital; and the printers and designers of popular engravings, from

Ha Bac province, which borders Hanoi on the northeast.

Today all of these guilds have moved elsewhere, thereby altering the

appearance of the neighborhood. In 1954,

Nhan dan [The

People], the official organ of the Communist Party, set up its seat

in this neighborhood along Returned Sword Lake. Nowadays one must go

to the village of Dong Ho, still in the province of Ha Bac, to find

the engravers and printers, one of the rare places which has

preserved this tradition. At the approach of Tet, their market comes

alive with traditional engravings marking the beginning of

festivities in vivid colors.

Other

streets have kept their names from days gone by. There is Hang Bac,

or Street of Silver (renamed Street of the Money-changers by the

French), which contained three separate guilds (for casting coins,

money changers, and gold and silver smiths), all from neighboring

provinces. The first group built a temple there to venerate the

founder of their profession, but ceased their activities in the 19

th

century after the transfer of the capital to Hue. The second guild

continued its operations during the colonial era, while the third

erected a temple in a neighboring street in homage to the founder of

their trade.

Hang

Gai (Street of Hemp) has a slightly more complex history. In olden

times, local artisans made and sold rope made of braided hemp. Later,

engraving and printing workshops were set up there in the 19

th

century. It was here that the imperial viceroy lived, across from the

residence of the French Résident Supérieur, the seat of

the new colonial power. As for Hang Chieu (Street of Mats), the

French renamed it in honor of the merchant and arms dealer Jean

Dupuis—instigator of the colonial conquest of the North—who

had opened a shop there in 1872. Hang Non (Street of Hats) was marked

by another memory, that of the “Red” labor union which

held its first congress there in 1929 at the house at number 15.

Revolutionary memories also enliven Hang Ruoi (Street of the Beetle

Grub)—so named because every year in the ninth lunar month a

market was held to sell this popular delicacy. In 1930, the house at

number 4 on this street harbored the office of the newly-founded

Central Committee of the Communist Party.

Other

streets of old Hanoi had less political destinies. Hang Than (Street

of Coal) was originally a pier where limestone was delivered to ovens

set up all along the river, then it became a coal market. Then there

is Hang Giay (Street of Paper), where shopkeepers sold paper that

they had bought from the artisans who lived in the village of Buoi,

situated at the extreme western edge of West Lake. At the beginning

of the colonial era, the street housed many

Maisons des

Chanteuses,

before they were moved to the outskirts of town during the 1920s.

Curiously,

today there is no street in Hanoi called the Street of Rice.

Previously, the commerce dealing with this important grain took place

either in the central market, where the consumers usually dealt

directly with the producers, or on the docks along the river. During

colonial times there was a Street of Rice (Hang Gao), which passed in

front of the market of Dong Xuan. The street eventually took the name

of the market after independence and following the collectivization

of the agricultural sector which brought about the disappearance of

the rice trade.

People

often speak of the “Thirty-six Neighborhoods of Hanoi,”

an expression which has been in use since the 15

th century

and which underscores the importance of the

phuong in Hanoi’s

history. Each of these neighborhoods has been shaped by history, by

the complex forces of immigration, trade, and political changes. The

expression took on even greater popularity in the 1940s after the

writer Thach Lam used it as a title for one of his stories.

Notes