Publications

Publications

Ouvrages

Ouvrages

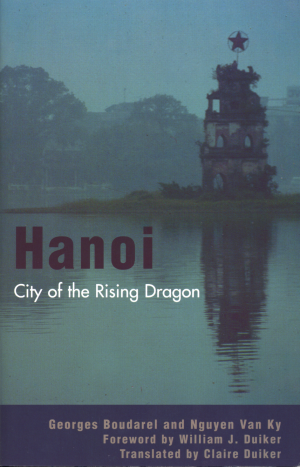

Hanoi. City of the Rising Dragon.

Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.,

2002, 187 p.

with G. Boudarel (1926-2003), foreword by William J. Duiker,

translated by Claire Duiker

Hanoi. City of the Rising Dragon.

Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.,

2002, 187 p.

with G. Boudarel (1926-2003), foreword by William J. Duiker,

translated by Claire Duiker

§ A City which Remembers

The Women of Hanoi

During

this same period, women were encouraged by the success of their

sisters in China and in the West, and began to break taboos and

demand their proper place in the family and in society. Taking

advantage of the new freedom of the press, they began to put into

question backward and oppressive customs, such as the commercial

exploitation of feminine virginity, early marriage where children

were regarded solely as objects of exchange, perpetual widowhood,

injustice, and the discrimination found in everyday life. In short,

they demanded equal rights and denounced ancestral practices which

affected them. Free love also made an appearance and young couples

began to assume a European air and go to the movies to see Western

films. They could been seen holding hands and strolling around

Returned Sword Lake, and then slipping into a hotel to spend their

first night of love together.

These

new freedoms had their price, however. Hanoi saw a dramatic increase

in female suicide: women who threw themselves into the river after a

first heartbreak, taking with them their secrets and lost loves. The

phenomenon reached such a height that men in Hanoi cynically began to

call local lakes “Tombs of Beauty” [

Mo hong nhan].

Still other women, led in a different direction, ran aground in

brothels or in dance halls.

Women

also began rejecting traditional constraints placed on fashion.

Vietnamese women had previously bound their breasts with a piece of

cloth (

yem) to hide them from the concupiscent gaze of men.

Modern women rejected what they considered to be both a physical and

moral constriction, provoking a reform in women’s fashion. It

was the designer Nguyen Cat Tuong [Lemur] who invented the tunic [

ao

dai], which then became the national dress of Vietnamese women.

He took inspiration from the traditional tunic with four panels, the

two front ones knotted at the waist; the new one only had two panels,

open at both sides from the waist down, and was fastened by the right

shoulder with snaps. His creation met with enormous success, and

still continues today.

This

emancipation of Vietnamese women and their revolt against the

traditional moral order were due to two factors: changes in the

educational system which began to accept female students, and

especially a change in mentality. In the 1920s, colonization brought

with it the establishment of Franco-Vietnamese education which,

though not a perfect system, still allowed women the opportunity to

obtain even the highest university degrees. In 1924, eleven of these

women from the schools of medicine, law, and literature, were

rewarded by a class trip to France. In 1935, it was ironically a

woman from Hanoi, Hoang Thi Nga, who was the first Vietnamese to

obtain a doctorate in science in Paris, after having finished

secondary school in Vietnam.

In

the time of the emperors, only men studied Chinese characters in the

hopes of passing the literary competitions which were the doorway to

respectability and prestige. Most women, with the exception of

singers and a few individual cases, were raised either to become

housewives or, at most, shopkeepers. For this reason there is not one

woman’s name inscribed on the 82 stone tablets erected at the

Temple of Literature which, since 1442, celebrate the memory and

glory of the valedictorians of each session of the mandarinal

competition. The educational system was solely a machine for

producing scholars imbued with Confucian doctrine, an edifice raised

by men against women, with women forever excluded. Along these same

lines, in the first half of this century it was often said that

“women don’t need much education.” If by chance a

rebellious woman was discovered trying to learn to read in secret by

the light of the hearth, her family would simply tear up her books.

What bothered parents the most was not the fact that their daughter

could read, but that they feared they would find her exchanging love

letters with a young man. It was of ultimate importance that their

progeny didn’t escape their control in matters of love.

In the more popular quarters, however, Confucian principles could not be

observed to the letter, as they ran contrary to many native beliefs

and traditions. Among the beliefs of the common people, for example,

half of all popular spirits were female .

One of the “four immortals” (

tu bat tu) was a

goddess, Lieu Hanh. This pantheon still remains important in the

countryside, having survived the campaign against superstition from

1945 – 1985. On the shores of West Lake, the temple of Phu Tay

Ho is dedicated to this goddess and is the site of a yearly

pilgrimage that attracts worshipers from around the country. Recent

years have seen the return of religious festivities, and the weeks

preceding Tet are often animated by the spirit of times gone by.

During

the war with America, Vietnamese women showed to the world that they,

too, could fight and defend their country. In a way, they were just

carrying on the tradition of their ancestors. History reveals that

some of the first historical figures in Vietnam are women, like the

Trung sisters. Throughout the North you can find temples dedicated to

these two national heroines, like the one in Hanoi mentioned above.

In recent years, the novelist Duong Thu Huong has become the

bête

noire of the regime, which is of course run by men. But she has

done nothing other than dare to say openly what her sisters thought

in silence.

Secret Loves

Despite

its history of combat, Hanoi is also a city of love. The city’s

parks and riverbanks are now swarming with young couples who are no

longer afraid to show their affection in public. This open display

has reached such a pitch that the street-sweepers refrain from

working near places conducive to intimate encounters. In a sense,

love has been forced outside into the streets, by promiscuity,

housing problems, nosy neighbors, and a certain sense of tradition.

The mores advocated by the Stalinist-Maoist reign were those of a

very prudish Confucian tradition whereby rules of conduct were

dictated by the leaders, under threat of severe punishment in case of

transgression. But the public saw that those who advocated this

decent behavior clearly felt above the law themselves. For example,

the former Party Secretary General Le Duan soon earned the reputation

of being a ladies’ man and a sensualist. He didn’t have a

harem, but the nurses assigned to give him daily massages understood

the situation clearly. So, while such dignitaries—clearly

disciples of Mao—could indulge in any pleasure they liked, the

common man had to hide any scandal for fear of being accused of

criminal licentiousness. In this moral universe women only had two

options: to be “virtuous,” i.e., live in denial of their

bodies and their passions; or to act on their impulses and be

considered as no better than common prostitutes.

In

Vietnam, as in the West, prostitution tends to reflect the society in

which it develops—including persecution under repressive

regimes. In the past, scholars often took singers as lovers, just as

some young people today find love with hostesses who work in bars

called

bia om, or “love cafés.” As a direct

consequence of social taboos, many live out their romantic adventures

in secret, outside of the traditional family circles. The most

cautious meet their lovers in cafés that are set up precisely

to facilitate discreet, amorous encounters. In general, behavior has

changed radically. It is no longer surprising to see couples holding

hands or walking arm-in-arm in public, something that would have been

unimaginable just ten years ago.

The

city of Hanoi itself is loved by its citizens, especially those who

have had to flee persecution. From books to poetry to songs, the

Vietnamese sing the praises of their capital city. As testimonial to

this city of love, there are many songs which celebrate Hanoi’s

spirit of romance. The following excerpt, for example, evokes the

good-byes of a young couple from Hanoi whom destiny has separated:

Giac mo hoi huong, [The Dream of the Return] by Vu Thanh.

He left his dear city one morning

When the autumn winds returned

The heart of the traveler was smitten with melancholy

He watched as his beloved

Disappeared into the smoky haze

Retreating into the distance with uncertain steps

Tears in her eyes, tears of bitterness

Good-bye

One day, even if I am lost in the four corners of the world

I will return towards the horizon

To find once more my dreams of springtime

And forget the days, the months which fade

In sobs I think of her

Oh Hanoi!

Vu Bang

and The Twelve Nostalgias

Like

many of his generation, Vu Bang made his literary debut in the world

of journalism in Hanoi and Saigon in the 1930s. He then left Hanoi in

1954, part of the exodus towards Saigon, where he resided for the

rest of his life. The following tale, in homage to Hanoi and the

North, was begun in 1960. He finished it eleven years later, at the

height of the Vietnam war.

At

first, no one could believe it. Why should it matter whether you’re

here or somewhere else—it’s all the same country, what’s

the difference? Don’t you find everywhere, from the North to

the Center, eyes that speak with a sea of emotion and affection; and

from the Center to the South, laughter which is held back but still

reveals ardent charms?

But

no, when you are far from home you feel like a piece of rotten and

worm-eaten wood as old as time immemorial. . . .

The

wind in the night made you cold, water pounded the shore in squalls;

it is always sad to be on the docks. We loved each other and we

wanted to encourage each other, but we didn’t dare or didn’t

know how to say it. The woman only knew how to bow her head with a

long sigh, while the man stood silent and looked with sad eyes, like

the eyes of a ghost, the black night cradled by the song of crickets

and the tears of earthworms. Sadness, and lassitude persisted thus.

Until the day . . . when the first rains of the season inundated the

streets, while we were in a little shop tucked away by the edge of

the river Tan Thuan .

Sitting beside us, clients from the North felt dazed and lost. As if

this atmosphere were intolerable to them, to the point where they had

to find a pretext to speak. One

of them said:

- In the North, it’s probably the beginning of the rainy season.

- Another:

- But, Madame, the rain in the North is different.

- And the third:

- Everything is different. Stop talking about it. It makes me want to

cry.

- The fellow adventurer looked at his friend standing next to him; they

were both silent for they couldn’t manage to utter a single

word, yet they felt a kind of electricity which ran through their bodies.

They

didn’t need much, just the exchange of banalities amidst the

rain of a desolate afternoon, to reawaken the melancholic impressions

of a worm-eaten heart . . .

The

more nostalgic it is, the more one loves Hanoi, and the more passion

one feels for the North. This nostalgia is disproportionate,

inexplicable! When you miss Hanoi and the North, it is as if you miss

your beloved: anyone at all can make you start thinking of her, and

she is, of course, the most beautiful of all. . .

I love Hanoi so much, and think so often of the North, that I cannot

appreciate all of the magnificent things that are presented to me

here. This is surely a grand injustice. And I end up loving this

injustice, and the twelve months and their climatic changes, the

harmonious vibrations of passing time, of birds, of beauty, of the

leaves, of sentiments, of love; I thank this injustice which has

allowed me to become aware of my ardent love for Hanoi. Oh Hanoi, you

hear me!

Notes

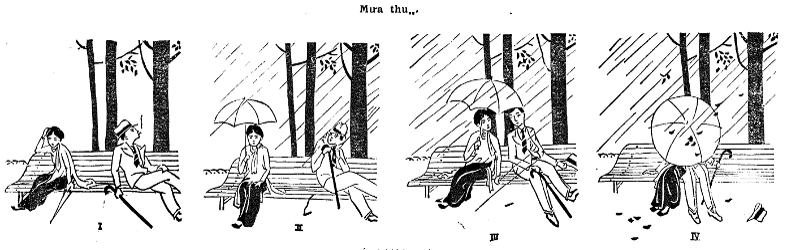

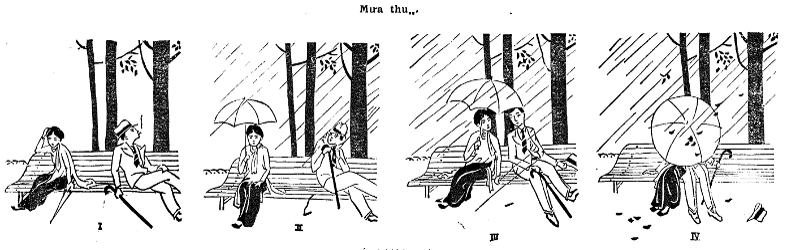

Illustration :

Phong hóa, n° 15, 20 sept 1932.

|

Sommaire de la rubrique

|

Haut de page

|