Publications

Publications

Ouvrages

Ouvrages

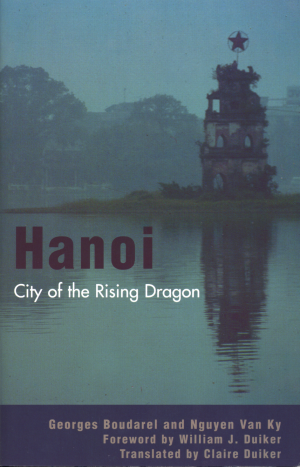

Hanoi. City of the Rising Dragon.

Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.,

2002, 187 p.

with G. Boudarel (1926-2003), foreword by William J. Duiker,

translated by Claire Duiker

Hanoi. City of the Rising Dragon.

Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.,

2002, 187 p.

with G. Boudarel (1926-2003), foreword by William J. Duiker,

translated by Claire Duiker

§ A City which Remembers

Villages and Labyrinths

Throughout

its history, the city has been assaulted and infiltrated by the

countryside. In 1946, one year after independence, legislative

elections included the participation of 118 villages within the Hanoi

region. Certain areas of Hanoi even today retain the name of

“village” (

lang). After innumerable administrative

changes and re-partitioning since 1954, central Hanoi is currently

divided into five areas, which are themselves subdivided into

phuong.

The outskirts are divided into five districts which are split into

communes of one or two villages.

The

houses of Hanoi, most of which look modest from the outside judging

by the size of their façades, nonetheless hold many surprises

for those who enter for the first time. Many of them are up to 50

meters [160 feet] long. This is why they are called

nha ong

(tube houses). This way of occupying space is actually Chinese in

origin, and was adopted by the Vietnamese only after long domination

by the Middle Kingdom. Traditionally, the Vietnamese prefer rather

wider constructions which are less deep, like the houses found in the

countryside.

In

the summer, storms and torrential rains inundate the streets and

refresh the city when it is overwhelmed by the heat. In the winter,

on the other hand, the leaden sky and melancholic mist plunge the

city into a kind of depression. The paintings of Bui Xuan Phai

are dominated by gray, and illustrate the type of architecture that

one finds in old Hanoi: small houses pressed together with roofs of

unequal height which form a jagged skyline. Years ago, the roofs were

of thatch and the walls of clay. Only rich people had the means to

build permanent structures, with wooden frames, tiled roofs, and

paved floors. When the French arrived in the 19

th century,

a good part of the houses in these working-class neighborhood were

just thatched huts.

These

many neighborhoods are linked together by innumerable little

alleyways (

ngo) which accentuate the depth of the houses and

their chaotic placement. Kham Thien Street, known for its

Maisons

des Chanteuses in the 30s and bombed in December 1972 by an

American B-52, has no less than twenty-six of these little alleys. It

was a veritable labyrinth, which became a real advantage in colonial

times with the creation of opium dens and brothels: this construction

allowed the inhabitants to escape from the control of the

authorities.

The

picturesque charm of these old houses has helped to shape the city’s

identity. If Hanoi bristled with gigantic high-rises it would lose

its soul. There is great concern today about protecting the old city,

which is now confronted by new economic pressures. Many Hanoi

residents, for example, complain about the number of new building

complexes erected in recent years around West Lake. Some progress has

been made, like when authorities gave in to public protest and set a

height restriction on a new hotel near Returned Sword lake from

twelve stories to five. In fact, old Hanoi has just been classed as a

historical monument by the city, thanks to the efforts of some

concerned citizens and the support of a Swedish organization.

As

a result of this new sensitivity to Hanoi’s historical

importance, the extension of the capital will take place out towards

the west. According to a recent urban plan, the Hanoi of the 21

st

century (business center, industrial zone, university, lodging for

some 200,000 people) will be built in the region of Xuan Mai, some

fifty kilometers [30 miles] from Hanoi. There is greater problem,

however, that faces the city now, one that goes beyond the

picturesque: Hanoi already has more than two million people and

continues to grow, straining the city’s limits.

The City and its Cuisine

One

cannot speak about Hanoi without mentioning one of its most

appreciated pleasures: extraordinary cuisine. In fact, it first

entered into Vietnamese literature because of its reputation as a

city of gourmets. Thach Lam dedicated many pages to it in his

The

Thirty-six Neighborhoods of Hanoi. And more recently, Vu Bang

wrote a long tale called

Mieng ngon Ha Noi [Gastronomy in

Hanoi], when seized by nostalgia for his native North while he lived

in the South in the 1960s. More recently still, Duong Thu Huong has

also paid homage to this aspect of the city in her novel

Paradise

of the Blind.

The

cuisine in Hanoi is not only famous for its diversity, but also for

the subtlety and richness of its flavors. There are specific drinks

and dishes which correspond to almost any moment of the day and

night, to every season, to each sex, and practically to every age.

The city also benefits from having a wide variety of shops: the

shopkeeper from Hanoi knows how to focus on his own specialty while

working in tacit solidarity with neighboring shopkeepers, even though

they may be his competitors. For example, a stall which specializes

in the famous Tonkin-style soup called

pho usually

doesn’t serve any drinks. If a client is thirsty, the owner of

the stall simply orders something from a neighboring stall which does

serve drinks. If the client desires to drink tea or smoke a water

pipe, an old woman sitting close by will serve him. Undoubtedly, the

charm of these open-air restaurants is not enough to stave off the

invasion of foreign ways, especially now during these times of

economic openness. In Vietnam, as in all of Southeast Asia, whiskey

is now served as a mark of social distinction. This westernization,

however, is only a slight alteration of a Vietnamese tradition. In

Southeast Asia, guests at a banquet used to drink rice wine, but now

with the introduction of European goods wealthier individuals

substitute whiskey as a sign of modern

savoir-vivre.

Another

popular drink is made from the juice of sugar cane. In the summer it

is squeezed and lightly scented with the juice and zest of a lemon,

making a great thirst-quencher. In the winter it is steamed or

roasted over a fire, sending out a tantalizing aroma that tempts many

a customer. On the way to school and throughout the day, children

chew on long pieces of sugar cane which have been peeled and cut into

round slices.

The

most popular alcoholic drink in Hanoi is beer. Introduced by the West

in the 19

th century, the famous “33” from the

French brewery of colonial times is back again, under the new brand

name “333.” The Vietnamese call it “three-three”

and drink it with ice-cubes. Groups of men love to get together

around glasses of “three-three” in the stalls offering

dishes prepared with goat meat—whose Vietnamese name (

de)

in slang means “lecherous.” A certain ritual presides at

these get-togethers. You generally start with a small glass of rice

wine mixed with goat’s blood, a mixture which supposedly aids

virility. To celebrate an exceptional occasion, they prefer snake;

you drink the blood diluted in alcohol, a potion which is reputed to

relieve back-aches. After that, they enjoy an order of the “seven

dishes”—all snake—and, in good spirits, they invite

the guests of honor to drink a fermented mixture of snake and

traditional herbs “one hundred percent” (to the last

drop).

One

of Hanoi’s most famous local specialties is

cha ca:

pieces of fish grilled on a wood fire, served over a plate-warmer and

accompanied with noodles, herbs (chives, dill, coriander), and shrimp

sauce (

mam tom). It was so popular that in 1954 a street was

named after the restaurant La Vong, which up until very recently was

the only place which would serve it .

Doan Xuan Phuc, founder of the restaurant, came from peasant stock

from the Bac Ninh region. He was a friend of De Tham, a Resistance

fighter who led a difficult life in the French forces and was

considered a pirate. When the latter was tracked down, Phuc had to

retreat to Hanoi. He then opened the restaurant which became a

meeting place for secret contacts among partisans. After the capture

of De Tham and his execution in 1913, Phuc settled permanently in

Hanoi as a restaurateur. His descendents have continued the family

business and are thriving.

With

the new open economy, the little alley called

Cam chi regained

its reputation as the site of a million flavors. From early morning

until late at night the merchants work in shifts to provide their

various specialties to a busy clientele. You find everything there:

from cheap rice cakes to the most gourmet meals, like chicken,

pigeon, or duck sautéed with traditional herbs, as well as a

wide variety of noodle soups. The alleys are also a common place for

getting together with friends. This is where the young motorcyclists

who race through town during the day, provoking both terror and

fascination, meet each other to elude the police who have been sent

out after them.

Rituals of the Table

Like

many other Asian cities, Hanoi is a morning city. Long before the

loud-speakers begin to broadcast official announcements, you can hear

the cries of the itinerant merchants ringing out in the alleyways to

wake the taste-buds. Each merchant has his own neighborhood and

clientele. They propose a whole range of “sticky rice:”

plain, with soy sauce, with sesame, with peanuts, with grilled

shallots, etc. Between errands, many Hanoi residents seek out these

ambulant merchants for a bowl of noodles with crab (

bun rieu cua)

or with snails (

bun oc); these are two dishes typically eaten

by women but which are equally appreciated by men. In his book

The

Thirty-six Neighborhoods of Hanoi, Thach Lam writes:

If you pass by the Maisons des Chanteuses or

brothels during the afternoon lull or late in the evening, you can

see women eating this dish [bun oc] with great care and

attention. The acidic broth makes their tired and heavily made-up

faces contort, and the hot peppers make their withered lips murmur

and whisper. The peppers sometimes even make tears roll down their

faces, tears that are more sincere than tears of love. The woman who

sells this dish has a tool, with a hammer at one end and a point at

the other. With one quick flick of this useful tool, the whole snail

falls into a bowl of bouillon. And yet even the quickest pace cannot

keep up with demand. As she watches her customers eat, she also wants

to have a bowl, she told me.

The morning is also the best time to savor

banh cuon, a kind of

ravioli served with grilled shallots and thin slices of pork paté

(

gio); you dunk the whole thing in fish sauce (

nuoc mam).

The afternoon is generally reserved for indulging in good food.

Between two meals many people snack on duck eggs, eaten with salt,

pepper, and sprigs of aromatic knotgrass. They also go in search of

che,

a candy made from soy or black bean, lotus grains, or

sticky rice. This typically Vietnamese dessert is served in small

bowls and perfumed with banana flavoring.

Autumn

is the nicest season in Hanoi, and the best loved. It too has its

special dishes. Early in the season, they harvest a kind of sticky

rice to make

com, identifiable by its green color, the color

of the leaves of the banana tree. This delicacy can be prepared in a

number of ways: some prefer it fried and lightly sweetened, others

eat it plain. Rich or poor, cultivated or not, no self-respecting

person from Hanoi can say no to this delight, which has almost become

a symbol of cultural identity.

Contrary

to Chinese cuisine, which is very rich and complicated, Vietnamese

cuisine—at least that of the common people—is prepared

with completely ordinary ingredients. People from Hanoi use their

ingenuity in the art of making the most out of the ingredients at

hand. For example, another typical dish from Hanoi is called

bun

cha. It is prepared with simple ingredients, small pieces of

grilled pork and served with noodles, lettuce, herbs, and the

ubiquitous fish sauce, but has an incomparable flavor. As in all

Vietnamese dishes, meat is an indispensable element, but it doesn’t

play the same role or occupy the same space as it does in Western

dishes. Its primary function is to give flavor, while the base

remains the rice: it is no surprise that in Hanoi (as in the rest of

Asia) they say "to eat" as "to eat rice" (

an

com).

Bun cha, for example, is made of vermicelli—but

the noodles are made from sticky rice. Passing by the Street of

Chickens (Hang Ga), clients can savor the aroma of this succulent

dish coming from a small shop run by an elderly couple. Out on the

sidewalk, the husband keeps an eye on the grill and from time to time

plugs in his little fan to stoke the fire; while inside the stall his

wife serves the clients, who call her

chi (big sister) or

co

(little paternal aunt). This division of labor is quite rare in

Hanoi, where traditionally women work hard throughout the day while

men pass their time in the drink stalls. This couple has even

declined the offer of a businessman who wanted to transform their

little stall into a mini-hotel, and are content to live off of their

small business.

Pho

by Nguyen Tuan

Pho

is also a very popular dish . . . Many of our fellow citizens have

been eating

pho since they were children, at that tender young

age when one hasn’t yet tasted life’s disappointments or

known need; unlike adults, who are well acquainted with problems that

taste of onion and spice, of bitter lemons, or of hot peppers. Even

poor children can make do with meatless

pho.

You can eat

pho at any time of the day: early in the morning, at

noon, in the evening, or late at night. . . No one would dare to

refuse the invitation of an acquaintance to go have a bowl of

pho.

It permits those of modest means to be able to express their

sincerity towards their friends. It is also great because it has a

different meaning in every season. In the summer, a bowl of

pho

makes you sweat, and when you feel a gentle breeze brush your face

and back you feel like the sky is airing you out. In winter, a nice

hot bowl of

pho brings color to pale and cold lips, and warms

up poor people like an overcoat. . .

Pho

has rules all its own, like in the names of the stalls. The name of a

pho

vendor’s stall usually only has one syllable—its

“popular” name—or is sometimes named after the

vendor’s son: for example

Pho Phuc

[the

pho of Happiness],

Pho Loc [pho of Generosity],

Pho

Tho [

Pho of Longevity]. . . Sometimes

they are named after the vendor’s physical deformity:

Pho Gu

[

Pho of the Hunchback],

Pho Lap [

Pho of the Stammerer],

Pho Sut [

Pho

of the Hare-Lip] . . . Sometimes people give the vendors nicknames

based on where they usually set up: Mister Pho from the Hospital,

Mister

Pho of the Gate, the

Young

Pho Under the Bridge. . .

Sometimes the name is taken from a distinctive way that the vendor

dresses. One vendor became known for the hat that he wore during the

French colonial period, called a

calot, and has since enjoyed

an unparalleled reputation in the whole capital as

Pho Calot.

One

of the best things about

pho is that you can transgress the

rules while still remaining true to this special dish. I think that

this principle rests on the fact that it must be prepared with beef.

Maybe

pho would be better with the meat of other animals

(four-legged, winged, etc.), but if it is

pho, it must be

prepared with beef. Is it then a transgression of the rules when it

is prepared with duck, with Chinese-style pork, or with rat? . . .

The working classes are attached to classic

pho. Today, some

people experiment by seasoning it with soy sauce and Chinese

ingredients; this is the privilege of the rich. . . In reality, the

true flavor of

pho for a connaisseur is that of cooked beef,

which is more aromatic than boiled beef and has an odor that carries

the spirit of

pho. Moreover, artists find that cooked beef

presents itself better aesthetically than boiled beef. In general,

vendors without respect for their craft first cut the cooked beef

into small formless pieces, and when the clients arrive they just

toss them into the bowls; this isn’t important for those who

are just trying to fill their stomachs as quickly as they can. But

when a finicky customer arrives (a vendor can always tell when a

client is demanding, even if he has never seen him before), the

vendor places his knife on a nice piece of cooked beef and slices it

into thin, wide pieces, with the pleasure of someone who takes pride

in his work.

One

intellectual who was worried about the future once wondered “if

one day, when the nation’s economy reaches the ultimate stage

of socialism, our national

pho will be in danger of

disappearing, and if we will eat canned

pho that you have to

heat up in boiling water before opening it, which would make the

noodles swell up.” He was harshly answered by one of the

clients in a stall: “Go to hell! Quit speculating about the day

when the sky will fall on our heads. . . As long as there are

Vietnamese, there will be

pho. In the future

pho will

be as hot as it is today, and maybe even more delicious. Our bowl of

pho

will never be put into a can, American style; as a true

native of Hanoi, I can assure you that this bastardization will never

happen.”

Whenever I start talking about

pho, I always end up thinking of a good

friend with whom I used to eat

pho and talk for hours about

everything and nothing. Like many people, she left for the South out

of pride. Now each time I discover a clean little stall that makes

good

pho I can’t help thinking of her, since she loved

really hot peppers. Out of superstition, she even attributed her

ability to make a living to the areas where they have hot peppers

which make your lips swell up. Every time I eat a spicy

pho

that burns my lips, my affection for this friend who left for the

South also grows stronger. . . I know that there is

pho in

the South, and even a southern style

pho, but the

pho

that you find on the sidewalk as an émigré is never as

good as the one you find in Hanoi—prepared in the traditional

way, eaten around a fire in the middle of downtown, in this “city

of a thousand-year-old culture.”

Notes

|

Sommaire de la rubrique

|

Haut de page

|

Suite

|