Publications

Publications

Ouvrages

Ouvrages

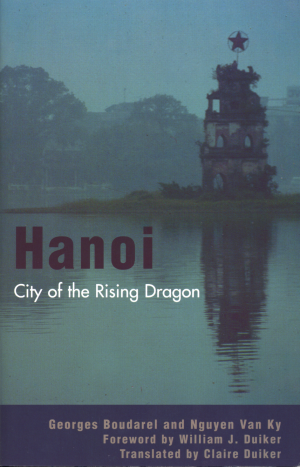

Hanoi. City of the Rising Dragon.

Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.,

2002, 187 p.

with G. Boudarel (1926-2003), foreword by William J. Duiker,

translated by Claire Duiker

Hanoi. City of the Rising Dragon.

Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.,

2002, 187 p.

with G. Boudarel (1926-2003), foreword by William J. Duiker,

translated by Claire Duiker

§ A City which Remembers

Flowering of Poets and Novelists

Hanoi

is also a land of culture, and in the 1930s experienced an incredible

blossoming of poets, novelists, and journalists. There is now renewed

interest and appreciation for these writers who, for decades, were

ignored or suppressed. Paradoxically, their rise was made possible by

their anti-colonialist ideas, which were hidden for a time so that

they could devote themselves to literary creation and the

re-examination of the cultural traditions of the past. They used two

newspapers as a forum for their ideas,

Phong hoa [Manners,

created in 1932, and

Ngay nay [Today], which was created in

1934 and reached a circulation of more than ten thousand—a

considerable number at the time. The figurehead of these progressive

writers was without contest Nguyen Tuong Tam, also known under his

pseudonym Nhat Linh. He took over the head of an

editorial committee made up of his two younger brothers, Nguyen Tuong

Long and Nguyen Tuong Lan ,

and with Tran Khanh Giu (alias Khai Hung), the poet Tu Mo, the

artists Nguyen Gia Tri and Nguyen Cat Tuong (alias Lemur), as well as

the poet The Lu. Together they elaborated an ambitious plan of action

and formulated simple and daring mottoes in order to develop a

literature in

quoc ngu; written by Vietnamese, for Vietnamese,

and nourished by themes taken from Vietnamese society:

--

the search for a new ideal

--

refusal to submit oneself to preconceived notions

--

refusal to serve anyone or to give one’s allegiance to any

power

--

guides for action: conscience, justice, and honesty

--

humor as means, laughter as weapon

The

newspaper

Phong hoa aimed its criticism at old-fashioned

cultural traditions and the outdated customs of society. It also

published press reviews, international and local news, stories,

poetry, and theater; all illustrated by caricatures, a first for the

Vietnamese press of the time. The success of the paper encouraged the

principal editors to form the group Tu Luc Van Doan [Self-reliant

literary group] in 1934, which became the driving force behind

literary creation both in Hanoi and in the whole country.

Determined

to break with classical forms weighed down by Chinese philosophical

and literary allusions, these writers fashioned a new, forceful style

marked by realism. Since they could not carry out a political

revolution, the set their sights on profound reforms regarding modes

of thinking, behavior, and beliefs. They attacked the constraints of

a society which suffocated individual aspirations in the name of

tradition. The characters of their novels became the spokesmen for

their thoughts. In

Doan tuyet [Rupture], Nhat Linh liberated

women from the weight of oppression of the family. Nguyen Cong Hoan

ridiculed the Mandarinate

and village notables in

Buoc duong cung [The Last Attempt

21],

a work which was immediately banned as soon as it appeared in print.

Ngo Tat To denounced outdated traditions in his many journalistic

writings, and criticized rigid literary competitions in his novel

Leu

chong [The Tent and the Cot]. Vu Trong Phung wrote about youth

faced with the problems of life in his novel

Vo de [The Dykes

Burst], while introducing a perfume of eroticism in

Giong to

[The Storm]. There were also exposés on the slums of Hanoi by

young journalists. Some of these books have since become classics

while others have been made into movies.

This

generation wanted to go beyond mere denunciation or criticism of

cultural traditions; their works advocated alternative solutions. For

some, the key to happiness was liberation from the yoke of

colonialism. Others advocated westernization, but in a limited

fashion and only as a catalyst for change, by which Vietnam would

become a truly modern society. In this manner, the political

revolution would begin from a cultural base. And it was in this

context of cultural change that modern poetry found a fertile soil

for its expression. Marked by the Romanticism of such French poets as

Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Verlaine, young authors discovered the

solitude of the individual in conflict with the community, the latter

representing constraint and anonymity. They thus usurped the position

once held by their elders, who were steeped in the strict rules of

classical poetry which went back to the Chinese literature of the

Tang dynasty. The famous literary competitions, now considered

antiquated in that era of profound change, were abolished in 1915 by

the colonizers, under the guise of a royal decree. What remained of

the past was now not much more than a faint glow of nostalgia. Some

of these old scholars had to become public scribes on the sidewalks

of the city just in order to survive. This climate of confusion and

reversal of norms is illustrated in a poem written in 1935 by Vu Dinh

Lien .

Ong Do [The Scholar]

Each year when the peach trees blossom

We see the old scholar

Spread out the ink and the red paper

On the sidewalk of well-traveled streets

Those who come by ask him to write

Compliment him on his talent

His fine touch sketches out the strokes

One would say a dancing phoenix,

Or dragons in flight

But year after year

What have the clients of yesteryear become?

Saddened, the red paper hides its sheen

The ink confines itself to the morose inkwell

The scholar is always there

Though no one notices him

The yellowed leaves fall on his paper

Outside the rain and dust pass by

This year the peach trees blossom

But the scholar has not returned

What has become of the souls

Of the people of days gone by?

The Intellectual Nguyen Tuong Tam

Nguyen

Tuong Tam was born on July 25, 1906 in the Cam Giang district,

between Hanoi and Hai Duong, from a long line of educated civil

servants and scholars. He was the third in a family of seven children

from the central Vietnamese city of Hoi An who came to settle in the

North. One of his ancestors had been Minister of the Army in Gia

Long. His father was a modest secretary in the provincial colonial

government. After his father’s premature death, Tam’s

mother had to raise the children by herself.

Tam began his studies in an apprenticeship of Chinese characters. A

gifted student, he continued Franco-Vietnamese education at the

School of the Protectorate.

His family’s modest financial situation forced him to take a

job as an employee at the Financial Office in 1924. It is at that

time that he met Ho Trong Hieu, the satirical poet who would become

known by the pseudonym Tu Mo. Their friendship was built around

discussions on literature and the importance of

quoc ngu

.

His first novel,

Nho phong [Confucian Manners], was published

in 1925; then a second,

Nguoi quay to [The Spinning-woman],

some time later.

In 1925 he enrolled at the Indochinese University, first as a student of

medicine before abandoning it for the School of Arts, created that

very year by Victor Tardieu. Finally, he interrupted his studies and

began to make a living in Saigon and then in Laos as a designer of

film posters. But his dream lay elsewhere. After getting married, he

left for France in 1927 with the help of his family and an

association which promoted studies abroad. He enrolled in the

Department of Sciences in Toulouse and graduated two years later.

According to his younger brother Nguyen Tuong Bach ,

he was impressed by the French social system, by the development of

democratic ideas, and by journalism, especially

Le Canard

enchaîné.

Upon his return to Vietnam in 1930, he taught at the private school Thang

Long, an institution that attracted a fringe group of intellectuals

involved in a variety of political movements. Among these

intellectuals, the most well known are Dang Thai Mai, a scholar

interested in Marxist theories; Hoang Minh Giam, an influential

leader in the Vietminh in 1945; Ton That Binh; and the Communist Vo

Nguyen Giap, future victor of Dien Bien Phu.

This was in the days following the Yen Bay uprising of 1930, led by the

Nationalist Party [Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang], and the formation of the

“soviets” of Nghe Tinh orchestrated by the nascent

Communist Party, two insurrectional movements which were suppressed

with brutality by the French. Fed on progressive ideas, Nguyen Tuong

Tam planned to launch a Vietnamese-language newspaper called

Tieng

cuoi [Laughter] with his brothers and friends. Authorization

being slow to come, he found a job as head of the journal

Phong

hoa [Manners] which was near bankruptcy. Completely re-done,

Phong

hoa appeared in July 1932 and is credited with being

the

first satirical journal illustrated with caricatures. Despite

threats, cuts, or suspensions imposed by the censors,

Phong hoa

aimed its criticism at those Vietnamese who collaborated with the

colonial power—in the absence of any capacity to undermine the

latter. The newspaper served as a reflection of the social and

cultural situation of the times, and made history by proposing the

creation of a modern society. In May 1935, after having attained a

circulation of 10,500 over a period of four years, it was finally

pulled out of circulation.

At the same time, Nguyen Tuong Tam’s literary output flourished

and grew in importance. He often wrote in collaboration with his

friend Khai Hung. In 1934, he also published with his friends another

newspaper,

Ngay nay [Today], which was similar in content to

Phong

hoa, in case the latter was shut down. This group

then founded the

Tu Luc Van Doan [Self-reliant literary group], whose

objective was to promote a national literature in the Vietnamese

language which focused on Vietnamese society. They were the only

group to have their own independent publishing house,

Doi nay

[Our Times], which allowed them to publish a large number of novels

and short stories.

It is natural that someone involved in so many intellectual pursuits

would eventually turn to politics, but Nguyen Tuong Tam was just

waiting for his time to come. When the Second World War broke out, he

was present at the foundation of the nationalist Dai Viet Party,

which rejected all forms of collaboration with foreign forces. In

1941, he rejoined survivors from the abortive Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang

uprising, who had withdrawn to China. Firmly opposed to shedding any

more blood in the name of politics, he sought support from the

Americans—the only ones he thought capable of facing up to the

Communists, who were committed to armed struggle. When the Vietminh

took power in 1945 after the surrender of Japan, he returned to his

country to reinforce the nationalist ranks.

The political situation was then awash in total confusion. The rival

nationalist factions made deals with the Vietminh in order to have

representation in the new government. At the same time, the Chinese

nationalist army of general Lu Han had been sent by the allies to

disarm the Japanese forces; they occupied Tonkin under the benevolent

watch of the Americans. In an atmosphere of secret operations and

intrigue, each party tried to take what it could get, but the

different nationalist factions could at least agree on one thing:

they had to beat the French in setting up an independent State.

After the August revolution of 1945, the declaration of independence of

September 2, and the elections of January 1946, Nguyen Tuong Tam was

named Minister of Foreign Affairs in the new coalition government.

His assistant was Pham Van Dong, a member of the Communist Party and

future Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Tam led

the Vietnamese delegation at the Dalat conference in April-May of the

same year, but his disagreement with the Communists convinced him to

flee again to China. There he found his two younger brothers, Nguyen

Tuong Long and Nguyen Tuong Bach.

After five years in exile, he returned secretly to his country in 1951 and

took refuge in Dalat. In 1956, he returned to Saigon and to his

career as publisher and writer. In 1960 he launched the political

movement

Mat tran quoc dan doan ket [National Solidarity

Front], to oppose the dictatorship of Ngo Dinh Diem. Accused of

subversive activities, he was called before a tribunal on July 8,

1963. On the eve of his trial, after having summoned his family and

friends, he put an end to his life. In a brief press communiqué,

he wrote: “I offer my life to History, which will be the judge.

I don’t leave the task to anyone else. The arrests and

condemnations of the opposition are serious crimes, which will end up

handing the country over to the Communists.”

Notes

Illustration :

Mạnh Quỳnh,

Croquis tonkinois, Ed. Alexandre de Rhodes, Hà Nội, 1944.

|

Sommaire de la rubrique

|

Haut de page

|

Suite

|